Vladimir Kozin is one of the most paradoxical artists of St. Petersburg who reinterprets the world of art history with irony. He is a member of the artistic group The New Stupid, the creator of the Mousetrap Museum of Contemporary Art, and founder of the PARAZIT gallery.

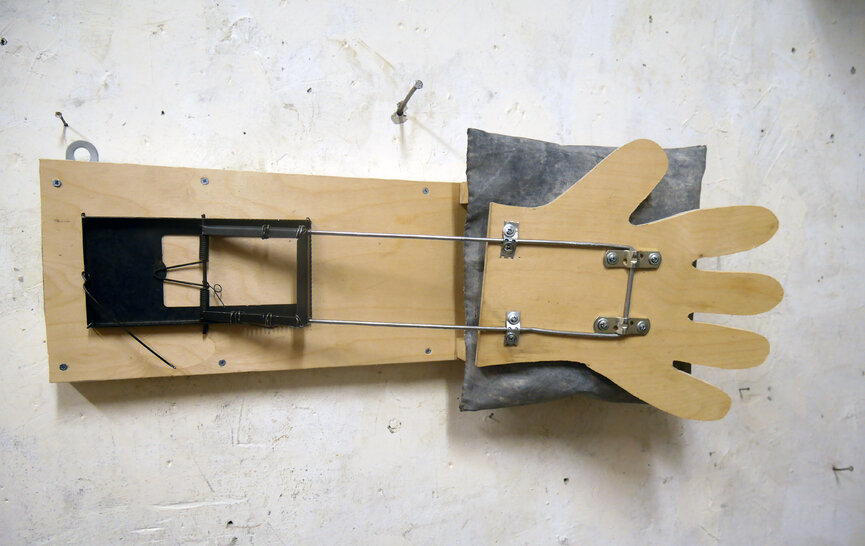

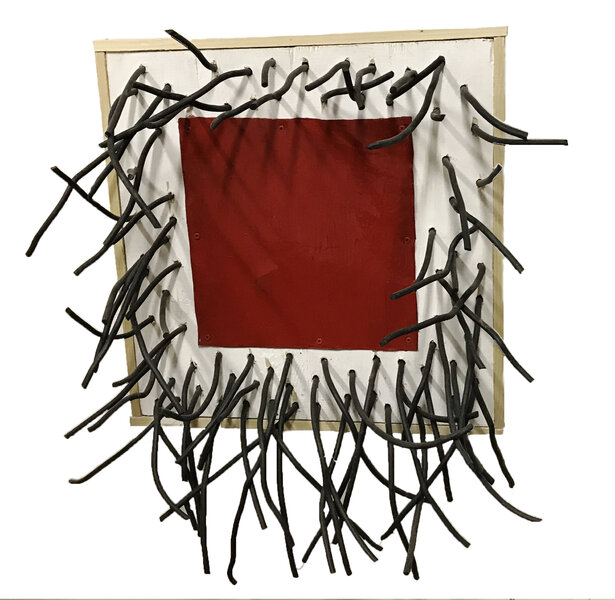

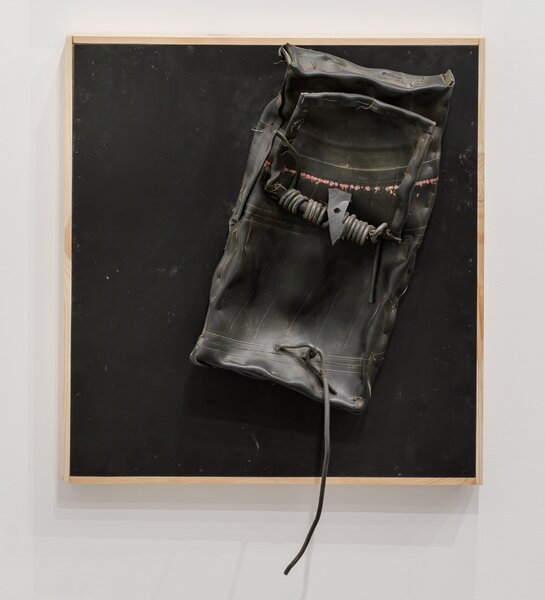

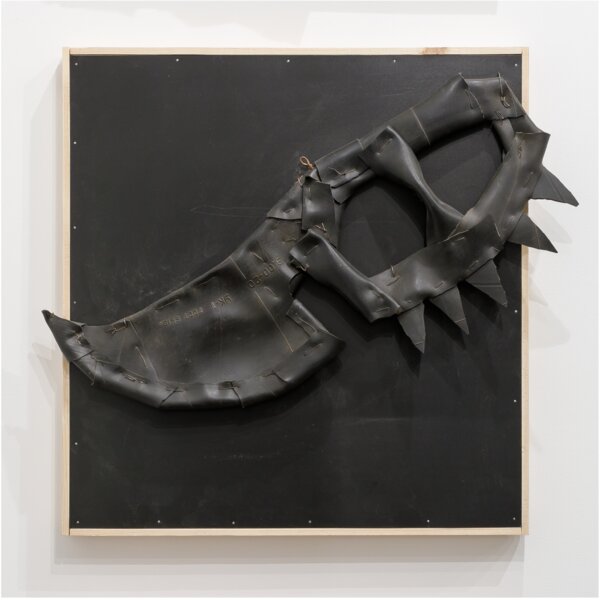

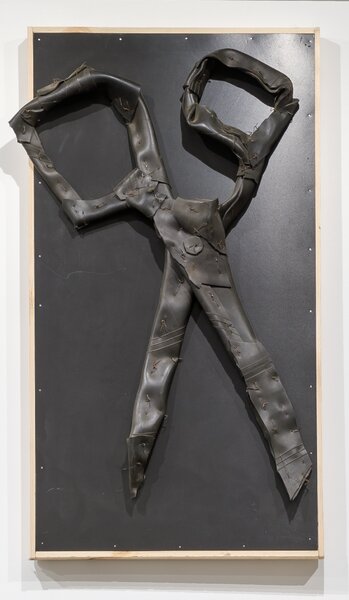

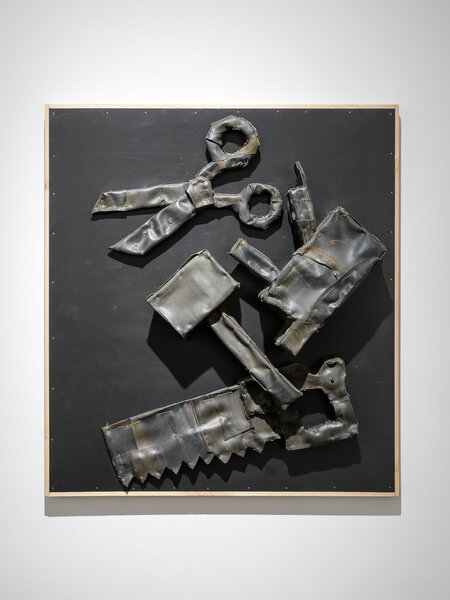

Kozin is known for practically having a patent on the use of materials such as car tires and plywood in contemporary Russian art. The cheap household material that seems unsuitable for creating high art in the traditional sense is the basis of his sculptural compositions, objects, and installations.

Kozin believes that poor art began with Van Gogh. Van Gogh's Boot is dedicated to the most famous pair of boots in art, painted in 1886. It was this painting that served as the basis for Martin Heidegger's reflection on the difference between a thing and a piece of art in The Origin of the Work of Art.

Kozin is a star of Russian Povera (an exhibition organized by Marat Guelman that marked an important trend in contemporary Russian art). The artist transforms everyday objects from lowly to lofty, using tires to create monuments to a teapot, an iceskate, and a razor... This tradition originates in the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, and Kozin repeatedly references this artist, along with Picasso, Malevich, and Tatlin.

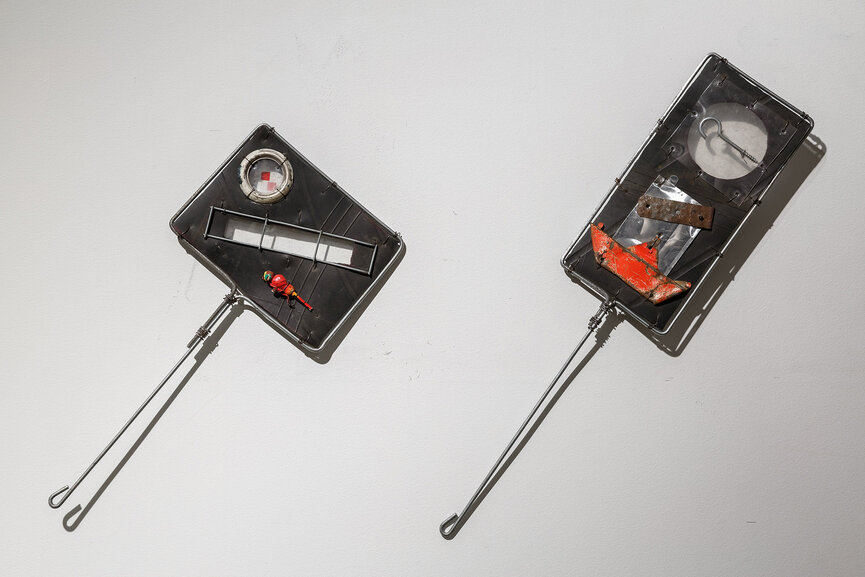

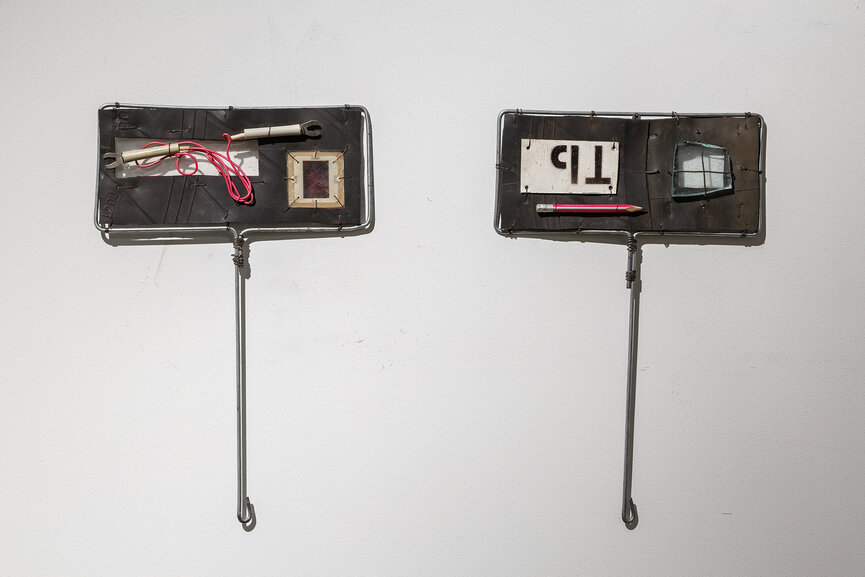

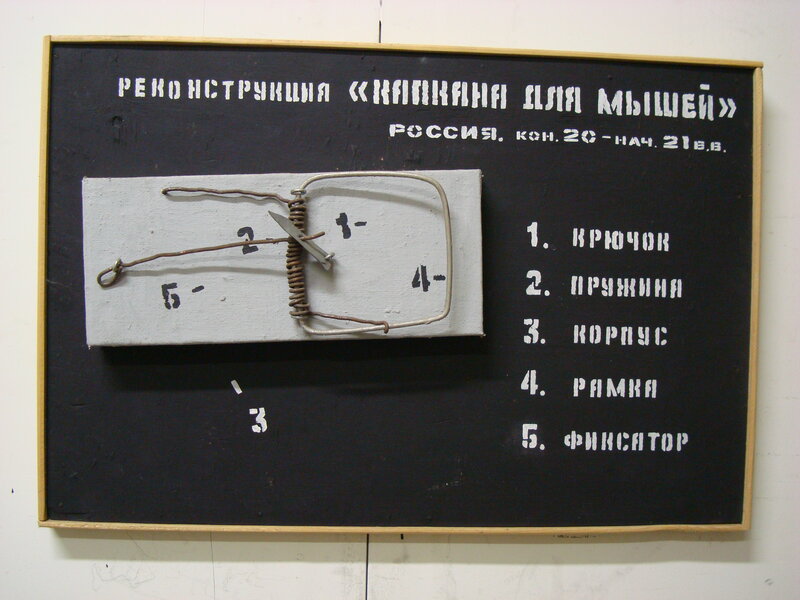

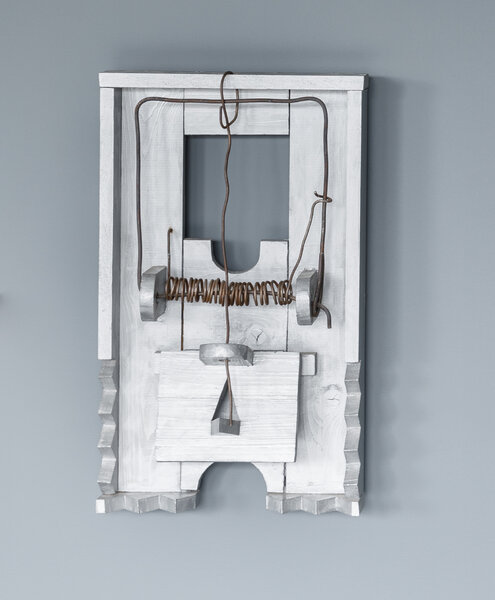

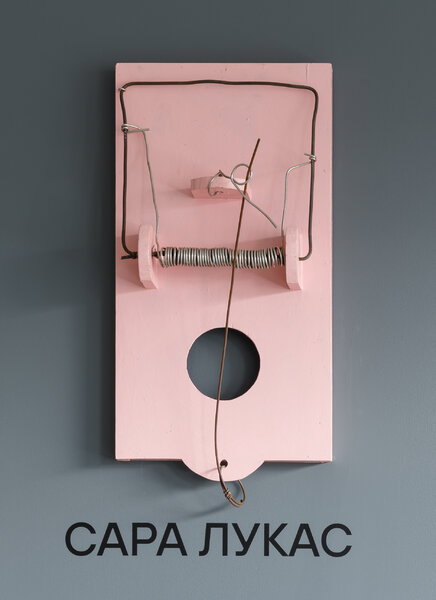

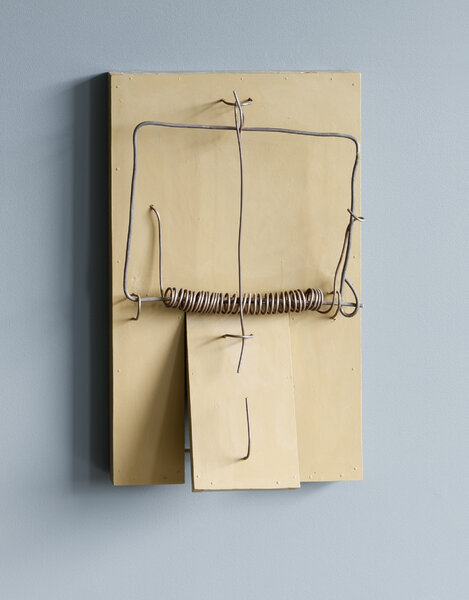

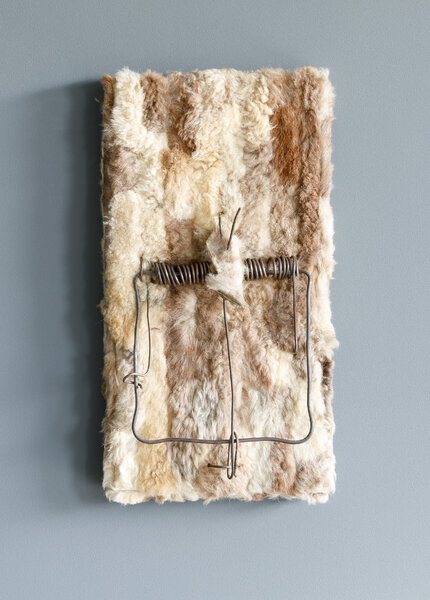

High and Low. Picasso's Guitar with a Fly Swatter and a Mousetrap demonstrates the alogism discovered by Malevich in Cow and Violin (1913), when incompatible objects are combined in a single work and the artist abandons normal logic. Matyushin, Malevich, Filonov the Mousetrap and Tatlin the Snare is homage to the main characters of the early twentieth century, while at the same time it is a dispute with the avant-garde, which declared war in art. Kozin is a pacifist who takes mousetraps and snares out of circulation as weapons of murder.

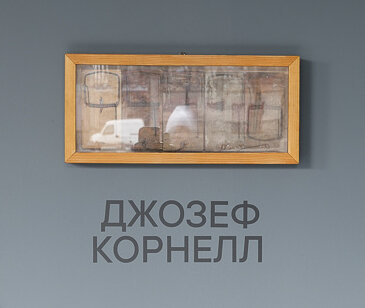

So, for the Mousetrap Museum of Contemporary Art that he founded in 2000, he bought mousetraps and distributed them to his artist friends to create works of art, thus transforming the art of war declared by man against the animal world into the history of art. In contrast to Claes Oldenburg's Mouse Museum (1965-77), it symbolizes not a heroic Disney mouse, but a weapon for destroying its living prototype. Reconstruction: A Trap for Mice is a conceptual work and a protest against murder, just like Little Pacifist – a child's shirt made from a car tire and hung by the sleeves with two mousetraps.

The snares and mousetraps placed along the artist's path are part of an ongoing theme for Kozin – finding one's place in the history of art. In a series of photographs taken in the toilet in his workshop, he posed the question: What makes me any worse than Rembrandt, Malevich, Kuindzhi, or Kabakov?

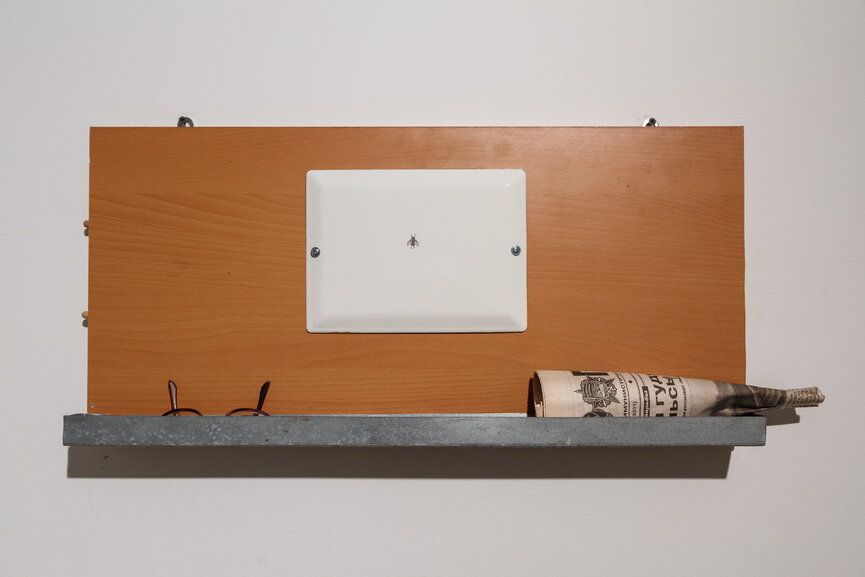

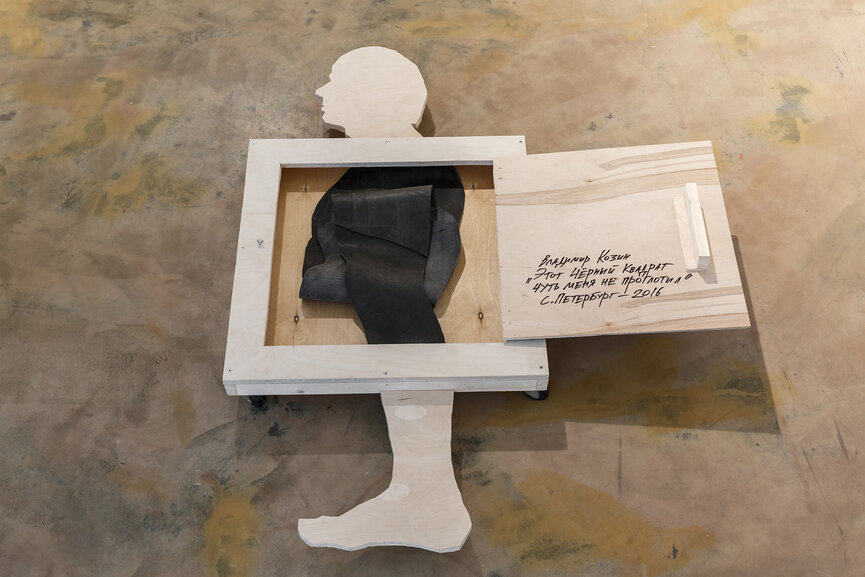

Exercise Equipment: Kill Your Inner Kabakov (the name was suggested by the sculptor Boris Orlov) is addressed to the work of the founder of Moscow conceptualism and one of the most famous Russian artists. Kabakov's fly depicted on enamel is set to be killed with a rolled-up Pravda newspaper. This ironic work conceals a frightening question-statement that was asserted in Kabakov's early text and in his installation Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future (2001). Kozin's response is Everyone will be taken into the future. However, this future is not a cloudless paradise, but a terrifying ideological hell: a series of plywood skulls pierced by ideology – the Soviet sickle, Trotsky's ice ax, Pol Pot's scythe... The plywood vanitas fit on the letters THE END as at the end of a film.

Plywood – the poor material used for displaying propaganda and making crafts at home – is also used to make the Portrait of Van Gogh With His Ear Cut Off as a Birdhouse and a Bird Feeder. This portrait recalls both cubist models, and Peter Pavlensky's Severance performance (2014), when he cut off his earlobe as a protest against the use of psychiatry in politics.

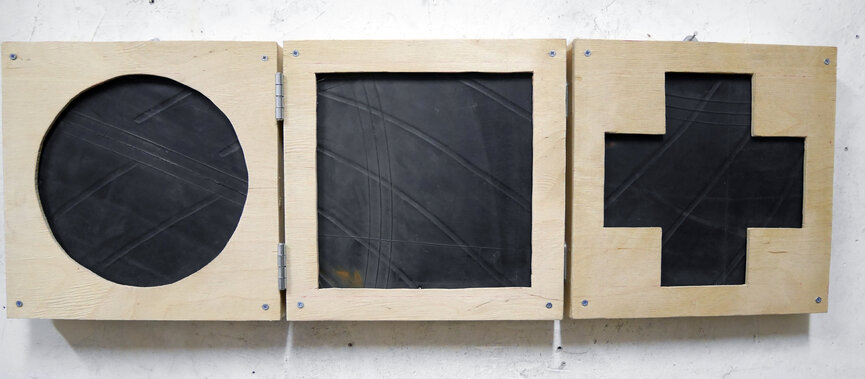

The artist touchingly attends to the utilitarian nature of his works. In the large-scale plywood Landscape with Salvador Dali's Persistence of Time and the Skull of Oleg the Prophet, the skull can serve as a home for amphibians. The wooden stool chained to the landscape includes the viewer in the work, not allowing you to leave the area of visibility. The changing viewpoint on art is what the modern artist has inherited from previous eras. He can pray to the Suprematist Diptych Icon, turn Morning in a Pine Forest into a lamp, electrify Black Square, and freeze Beuys' rubber Fat Chair with a refrigerator lightbulb, aware of the fact that Everything Has Its Time. This is the name of a series of vanitas played out with plastic skeletons on the theme of unmistakably recognizable works of art, whether it is Goya's Horror of War, Picasso's Girl on the Ball, or Mukhina's Worker and Kolkhoz Woman.

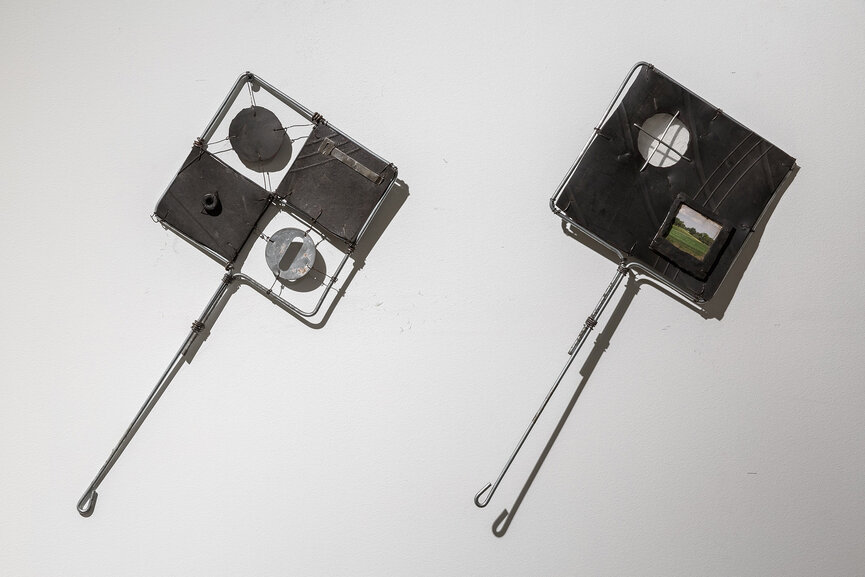

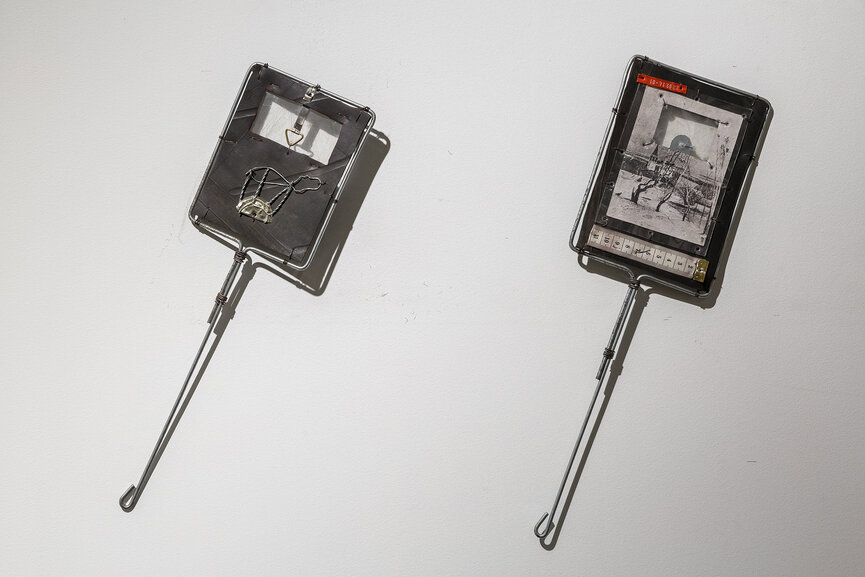

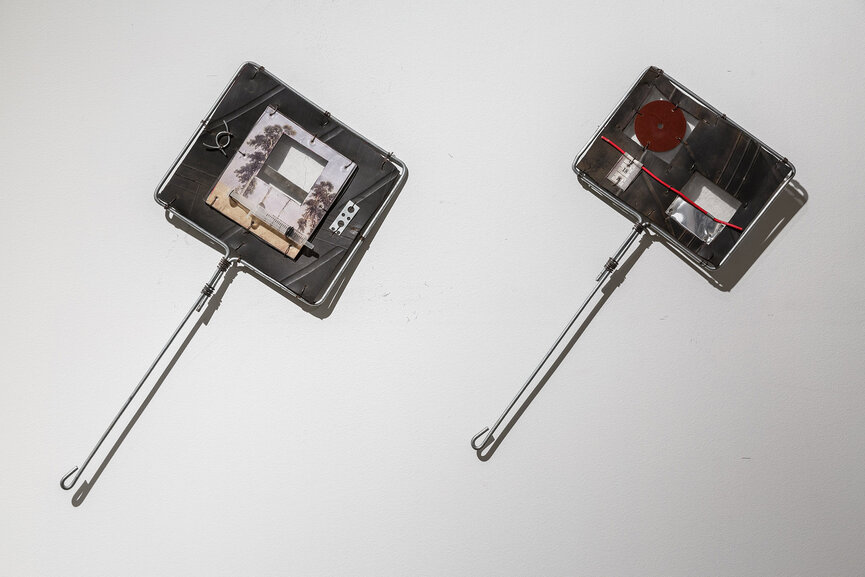

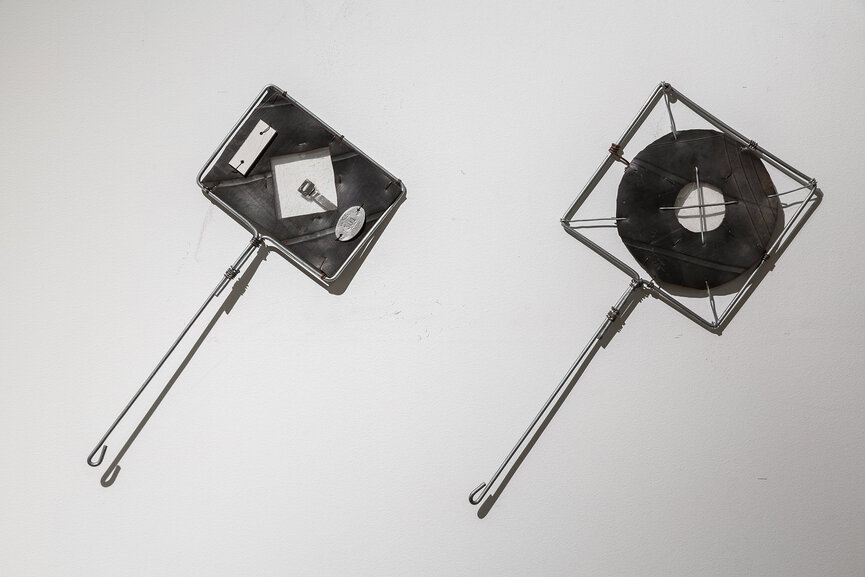

The artist is a viewfinder, and his purpose is to direct the point of view. Portable Viewfinders, which Kozin has been doing since the time of The New Stupid, let you look through the prism of visual images and the intersection of coordinates to see the artist's dream of great and pure art. This dream breaks up and argues with the famous statement of Theophile Gautier, who defended the ideal of pure art: Nothing is truly beautiful unless it cannot be used for anything; everything that is useful is ugly because it is the expression of some need, and those of man are ignoble and disgusting, like his poor and infirm nature. The most useful place in a house is the water-closet. It was actually Kozin's rubber toilet that was recently added to the collection of the Russian Museum, which stores the works of his heroes, the artists of the Russian avant-garde.

Olesya Turkina