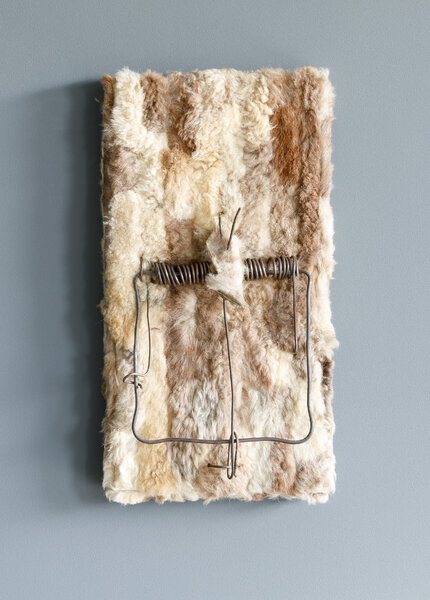

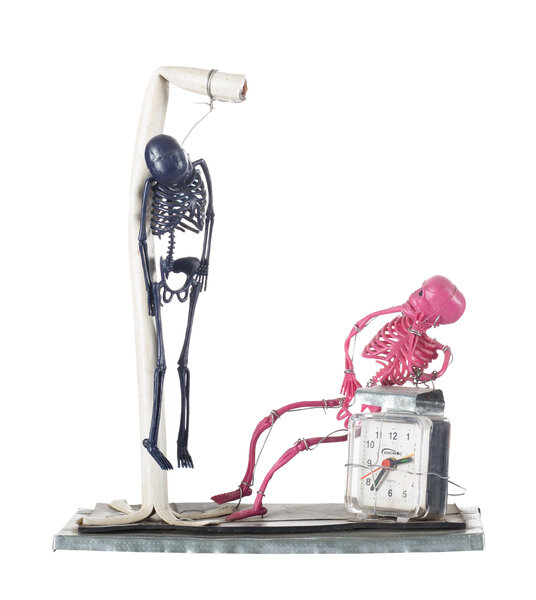

Viewers often associate an artist with one method or material, despite a long creative path and a diversity of practices. Manzoni is associated with excrement, Beuys with felt, Uecker with nails, and Christo with wrapping fabric. If Vladimir Kozin is to be reduced so mercilessly, then he is associated with rubber. His works made from the inner tubes of car tires appeared in museum and private collections all over the world, and continue to roam through numerous exhibitions, highly appreciated by connoisseurs of Russian contemporary art.

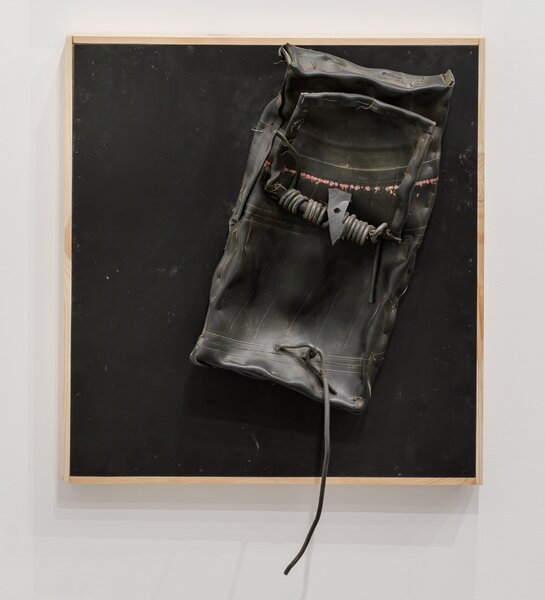

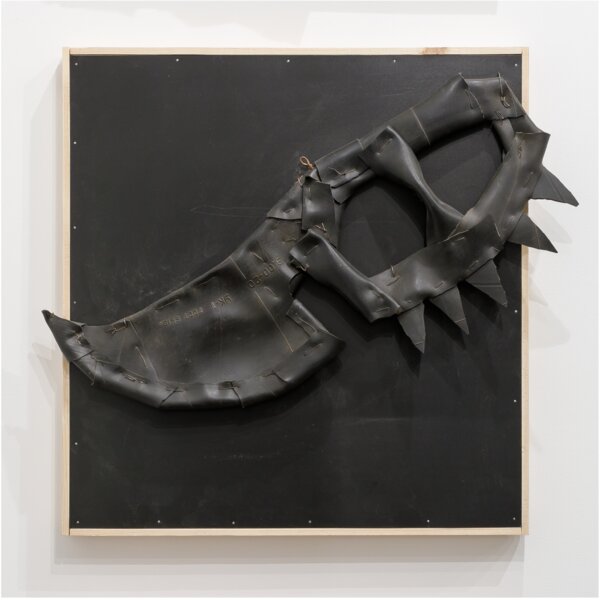

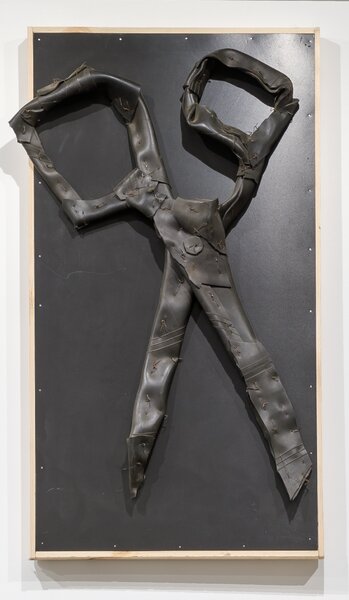

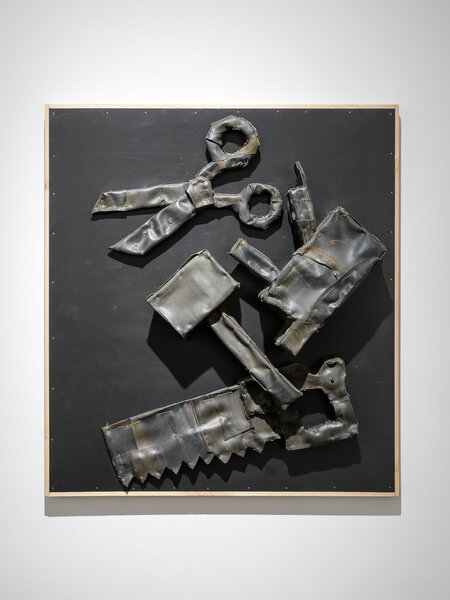

If in the past the rubber objects functioned in the exhibition space primarily as a large sculpture, now they have a background and have

turned into mountain reliefs, gloomily shining like beetles’ shells. The austere items are placed on a background as black as Malevich’s

square, as if they had frozen on the threshold of eternity. The perception gradually shifts from the “poor” subject and material into the unexpectedly majestic inner space of the work. A bra, a pubic louse, an axe, a pair of scissors come to resemble religious symbols. And even

the “moonlight” that seems cheerful at first glance, the cross-section of a rubber inner tube with an electric lamp placed inside it, at second

glass it starts to seem mystical. The unconcealed simplicity of the method only adds to this somewhat malevolent effect. Half of the objects presented in this series are weapons or tools for causing suffering. The artist has displayed automatic weapons, knives and pistols before, but they were exhibited in wire cages, like captured predators. Now they have been freed from restrictions and calmly demonstrate their full presence in contemporaneity.

The name of the project is not just a reference to the famous suprematist primary source. In the avantgarde and subsequent modernist movements, there was frequent discussion of the light emanating from a picture, which was not only reflected but also created by it. Kozin inverts this concept so that objects radiate darkness. By saying that black is white, the artist literally visualizes one of the most characteristic features of the experienced historical moment.

Техт: Alexander Dashevsky