There’s absolutely no doubt that Gorshkov has lost his mind, gone bonkers, totally lost it… But how could it be otherwise, if he says himself that he’s found “a crystal of pure craziness”, and intends to present it to the world? What else could you expect, if you can’t discover the crystal (within yourself) without losing your marbles?...

It is surprising how carelessly Gorshkov talks about the “crystal” – as easily and naturally as he combines one thing with any other in his works. This lightness is illusory, but hidden from the viewer’s gaze, because the approach that Gorshkov himself takes to the construction of the image, which took shape in “The Fountain of Everything”[1], paralyzes any attempt to work out how it is done. His works simply seem to happen. They are not devised and created step by step, but immediately appear as they are, on their own.

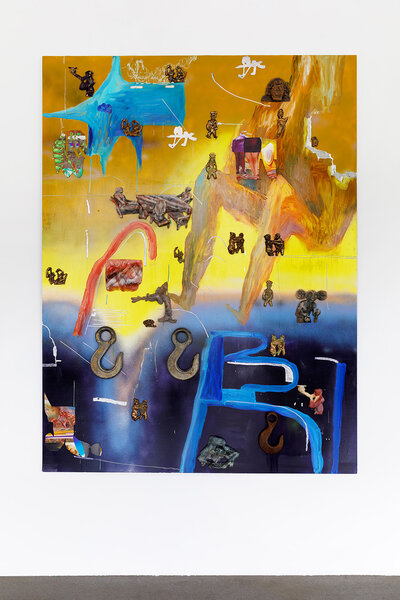

We may imagine how the production process takes place. The elements of the future flat works (there’s not enough imagination for sculpture) move along a conveyer belt. They are made of various materials and mainly rectangular in shape. Next to the conveyer belt is an enormous container with a “artistic mass”, consisting of art materials (paint, varnish) and non-art materials (putty, assembly foam, tar, artificial hair), found objects, fragments of craft works and borrowings, types of thinking, concepts, systems of world feeling and ideas. A mechanical arm moves the “mass” from the container to the conveyer belt, placing the contents in blocks that make a brief stop in its operation area. Despite the short production cycle, the process remains uncontrolled and is dependent on random events[2]. The way things end up is the way they stay. But the result is magnificent. Maybe it’s the crystal’s influence?

“A crystal of pure craziness” is a complete artistic gesture which only an artist is capable of. His transforming activity is like a mysterious alchemic reaction, turning ordinary things (workshop painting, memes and pictures from the Internet, items of furniture and everyday use, children’s toys, party items and other materials) into works of art. Its effect on the object is so strong that along with the nature of the object (initially mundane and functional, then artistic), its physical state also changes. The item becomes indecently beautiful, perfect, ideal. Tree stumps are covered in luxurious tar and stone sculptural details with emerald and amber patterns, noble bronze flashes with a warm and deep sheen, an aluminum surface shines in cold abstraction…. In the fantastic melting pot of the “crystal” everything is fused with everything else, and this fantastic combination of different visual cultures, images, sources, materials, languages and phenomena is almost completely impossible to understand.

This insuperable difficulty may remind us of the concept of the “aesthetics of absence” described by German composer and director Hainer Goebbels[3]. This is unexpected, because at first glance Gorshkov’s works do not suit being described in such terms: emptiness, disappearance, absence. However, the two authors are similar in their approaches to creating works designed to resist understanding in the sense of reducing content to what is already known. Goebbels talks of the empty center of the theatrical production, which arises when the figure of the actor is deprived of a dominant position on the stage. In a similar way, Gorshkov frees the traditional media of art from everything that served as the foundation of the classical concept of artistic perception, and primarily from the principles of organizing the painted surface.

Gorshkov’s works are excessive, they have so much happening in them that nothing actually happens at all. The viewer cannot single out and follow any story. All of them, and each one separately, are dissolved in a multilayered polyphony, causing the compositional structure to disappear (center, periphery; perspectives of distance and so on), along with the subject or theme, characters, primary and secondary details… And damn it all, Gorshkov does not give any hints about what to look for and/or where.

It's difficult to come to terms with this, because viewers want to see some kind of story, subject or scene. This is terribly annoying and enough to drive you mad, but you can’t look away – because of the visual attractiveness and strange magnetic attraction of the works. This attraction is strange, because they do not go against traditional concepts of Beauty, which has always been identified with well-proportioned form[4]. By doing away with this, Gorshkov brings viewers to the very edge of the abyss, he puts us face to face with the unknowable infinite, which has no limit and cannot be reduced to a rule that limits reality. Gorshkov leaves the world chaotic and incomprehensible, in order to find his own Beauty in the absence of order.

Gorshkov says that the “crystal” is always accompanied by gargoyles. The sharp, massive creations in chameleon colors greet the viewers, perhaps to protect the “treasure” from human interference. Perhaps they are warning us of its danger, that the treasure may be cursed if we cannot master the power concealed inside it?

[1] “The Fountain of Everything” – personal exhibition by Ivan Gorshkov at the Moscow Museum of Contemporary Art (10 Gogolevsky Bulvar) in 2019.

[2] I consider it important to give a description of the real production process, but it would interfere with the course of the narrative. To avoid this conflict, I will give the description in a footnote. The process of creating the work has many.stages – finding and collecting digital and material sources and manipulate them; redrawing the sources, their fragments and combinations with the help of an assistant; adjusting the painted image with additional color layers and/or details; preparing “overlays” – reliefs: molding and polishing objectives of bronze and artificial stone; trimming and stamping aluminum; painting and aging objects etc.; integrating “overlays” into the painted surface using glue, tar and other elaborate and specially invented adhesives; aerography etc. It seems this complex process cannot easily be reduced to a game of randomness and unpredictability in the creation of art.

[3] Hainer Goebbels, The Aesthetics of Absence.

[4] “According to common sense we judge a well-proportioned thing beautiful. This allows us to explain why since ancient times Beauty has been identified with proportion.” (see “A History of Beauty” by Umberto Eco).

Curator: Alexey Masliaev

Official partner of the exhibition WYNWOOD Hotel

\n