DOG’S SPOON

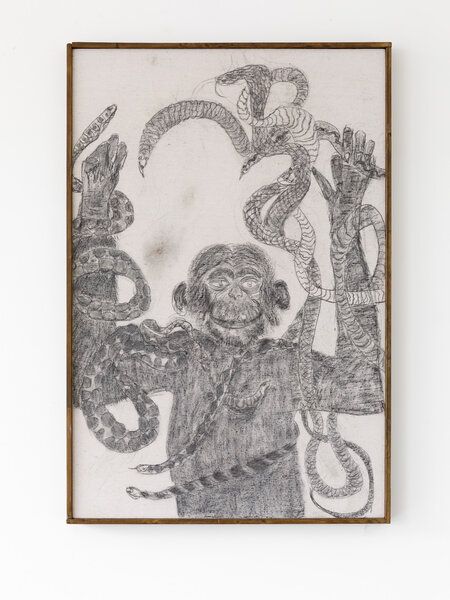

The exhibition “Dog’s Spoon” by Vika Begalska and Alexander Vilkin is an artistic contemplation of inhuman dimensions – sizes, languages, situations and signals. The name of the project sounds bizarre at first – what’s a “dog’s spoon”? It seems to be utterly meaningless, since dogs don’t eat with spoons, unlike people (and only people). But when we look at Begalska’s and Vilkin’s art, we also encounter people there – they are certainly strange, but they are still people. Then what’s the catch? Probably because although the artists depict people, the artworks are not really about people – or rather they are about situations when people become participants. Besides human characters, these situations feature with dancing skeletons, playful nuns, monkeys, dogs and donkeys. Often the characters are not immediately discernible – the dull colors and the gentle, barely noticeable contrasts immerse us in the pictures which eventually talk to us and tell us their stories. Begalska and Vilkin play with images, at the same time flirting with the viewers, allowing us to guess what the pictures are in fact saying to us in their own artistic language.

The phenomenon of language, or tongues, plays an important part in our discussion. A spoon, a simple, familiar piece of cutlery, comes into contact with the tongue, or rather with tongues. The first tongue of contact with the spoon is the eating tongue that senses taste, a greedy, healthy tongue. While it is eating, it makes no noises, it is mute, absorbed in the process. The other tongue is also mute, but for a different reason. This is the tongue of illness, epilepsy, convulsion – it is saved by a spoon that is placed between the jaws of a person having a fit. The third tongue is the tongue of the medical checkup, when the spoon is put down a person’s throat, while the throat makes the awkward “aaaaa” sound. All three tongues exist in three different dimensions and are connected by this simple cold metal object. The spoon becomes the conductor between tongues, but tongues which do not produce articulate speech, tongues of mute but still human life.

Inhuman life emerges somewhat later, somewhere nearby, on the periphery of our vision. It is also mute and capable only of producing inarticulate sounds, barking, bleating or squealing. Humans start to share their muteness with animals – and the spoon, this cause of human muteness, becomes a symbol of animal muteness. Animals, and skeletons along with them, these obvious images of death, sing and dance, opening their mouths at each other (as if playing at epilepsy, this human disease), entertain nuns, and entertain themselves. As if on the other side of the canvas, music plays, setting the tempo for the characters, although we do not hear it. Perhaps for it to be heard, we need to look for the missing link – the spoon that will keep our jaws apart and create this miracle of metanoia, an onset of mindlessness that brings together people and animals, dance and stupefaction, the tongue and the howl, death and unbridled joy. The mouths of the characters — painted mouths, inhuman mouths, animal mouths — are busy devouring, with a song or a spoon, measuring inhuman time inside the event of an inhuman game.

So what is actually happening in these artistic pastorals? Nuns possessed by devils go towards the light of fading lighthouses, skeletons mock donkeys, and the monkey tries to become a human being, but fails (perhaps because its time is up). We seem to be witnesses of dozens of micro-events, events which took place in a dimension where music is heard. At the same time, perhaps, our characters have not managed to understand this yet – to understand that the event has already taken place, that the light in the lighthouse has gone out, that the nun is only saved by lust combined with true faith, and that the monkey will never become a human being. The characters remain mute, like art itself – mute and lost, despite their feigned merriment. They are lost like the model romantic hero who was lost in his own time, but always found an escape – usually in his own death. We cannot know what escape these characters will find (and whether they will find one at all) – but we can keep the heads of some of them up, while the tender-hearted skeleton dances and opens their inhuman jaws one by one with his dog’s spoon.

Natalya Serkova