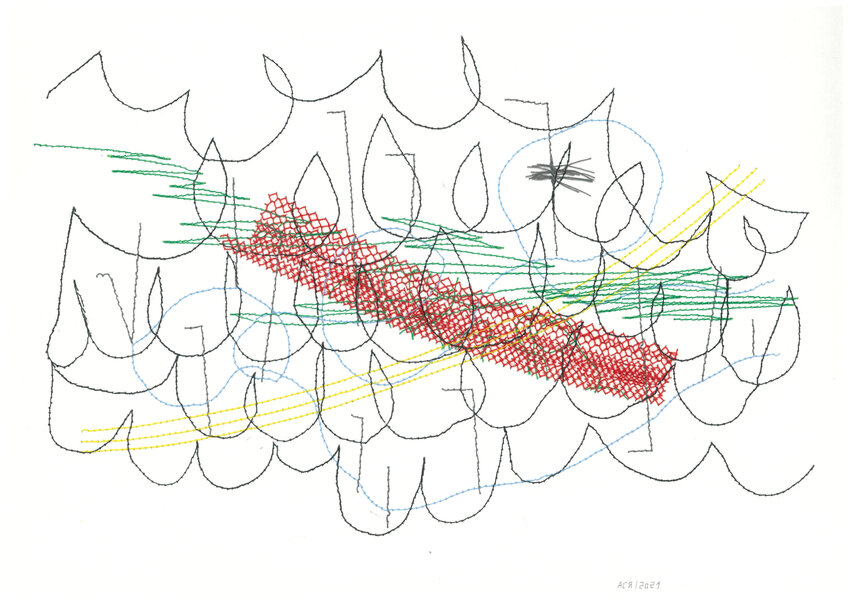

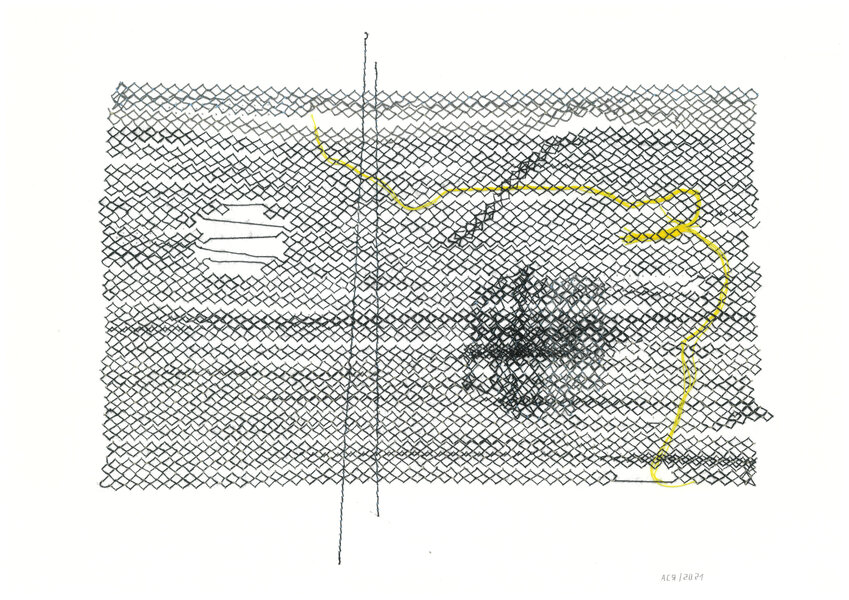

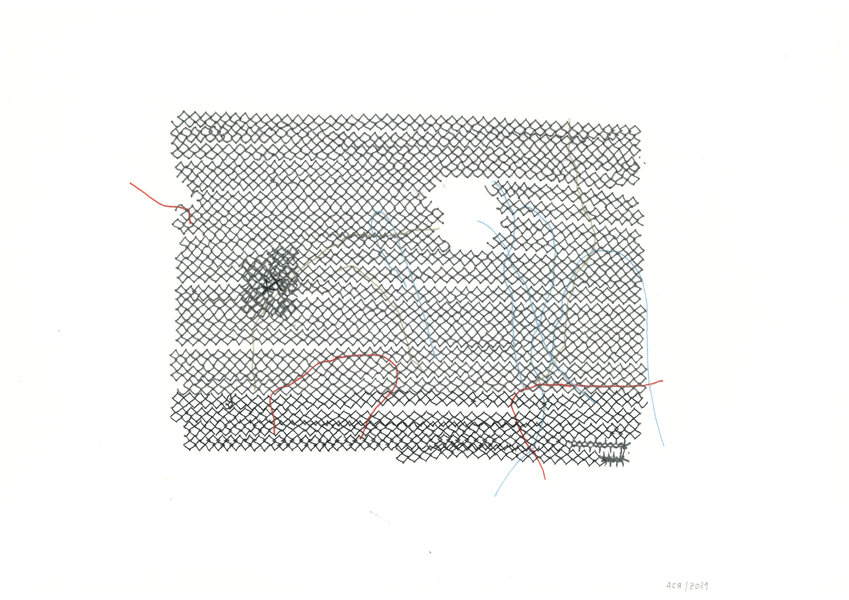

The Iron Overtones project is connected to artistic and real-life contexts in equal measure. In the artist's works, we can easily pick out visual elements familiar from childhood: 50 years ago or so, homes across the country were decorated with thin black iron work in the form of shelves, flower pots, and magazine racks. Their graphic nature, lightness, transparency and fragility signified a return to “culture one” after “culture two”, borrowing the terminology of Vladimir Paperny. Now these objects are viewed with a dose of nostalgia. The Soviet sensation of being in step with foreign fashion, design, and with the rest of the world was short-lived, but its naive aesthetics survived the times. Each cheap fence, border railing, window grille and stair banister demonstrates how generic abstract forms relay a lyrical narration, like the musical notes in the design of the music school seen by the artist in Murmansk. Music theory and scales have always had an undeniable cultural status in the eyes of parents who fail to understand how coercing children to create can kill their creativity. Iron overtones in the teacher’s voice both alienate and develop a bond, which is how an individual intonation emerges.

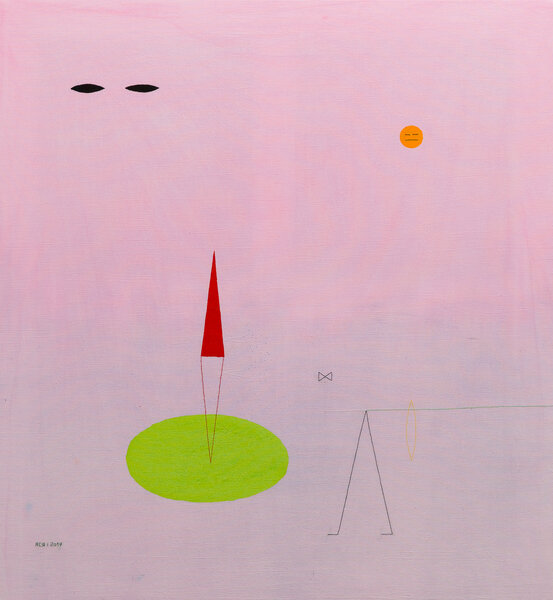

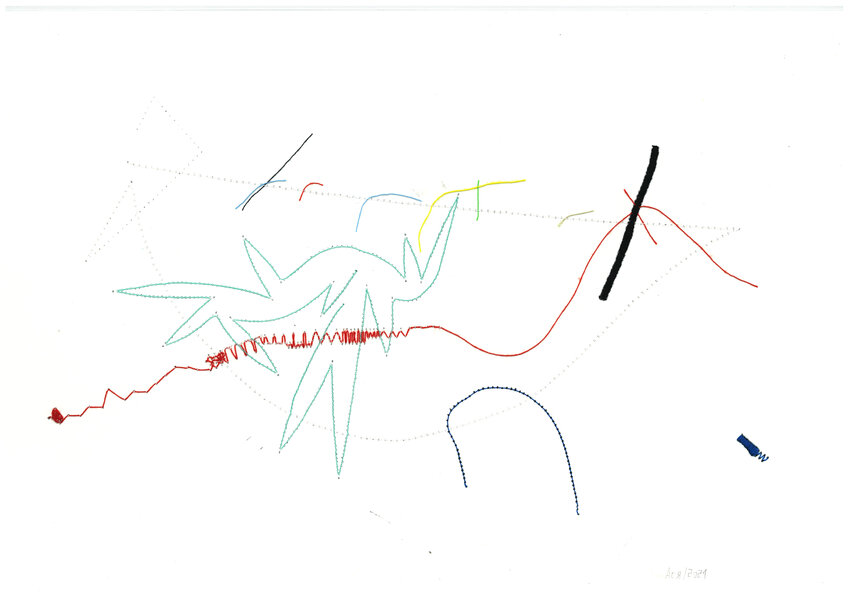

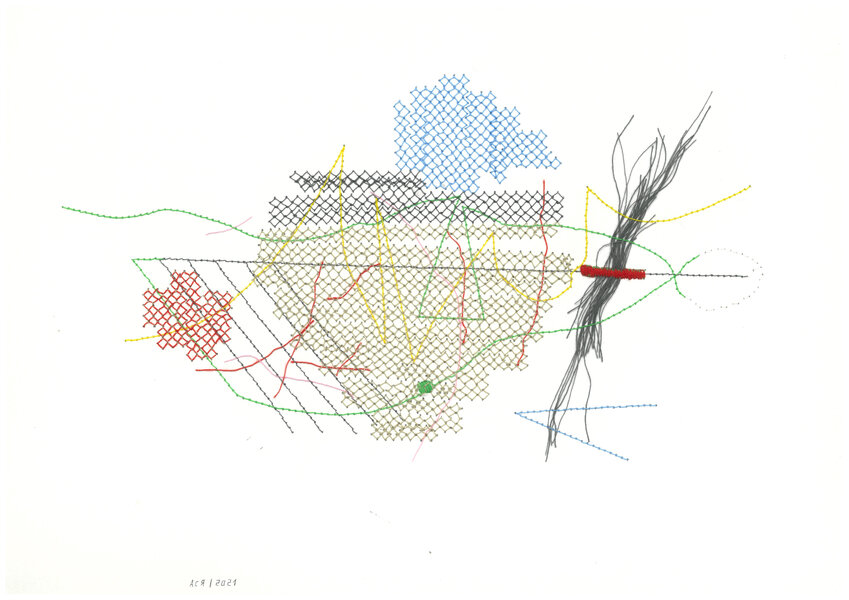

This world exists somewhere between the routine and the game, between the music school and the playground. Having survived several generations and multiple paint jobs, a metal construction can be filled in with some imagination to turn into a castle, then a store, a carriage, a sonic blaster, or absolutely anything. The objects depicted by Marakulina are animate as well — we see a set of characters whose relationships, dialogs, and movements were literally pulled off the street by the artist and then sent back where they came from. Their common source is the childhood pantheon of comic book heroes and video games like Pacman or Mario Brothers.

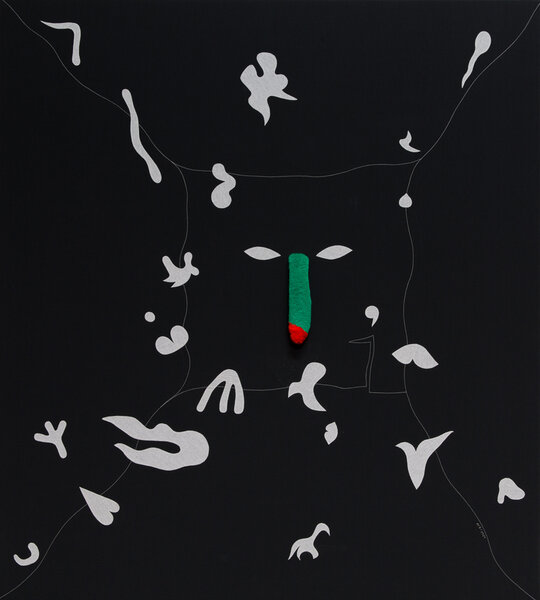

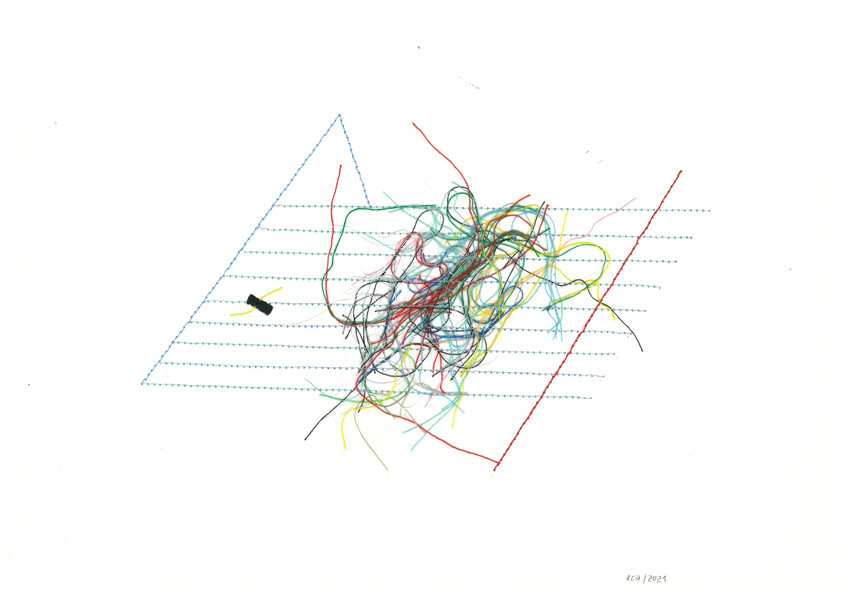

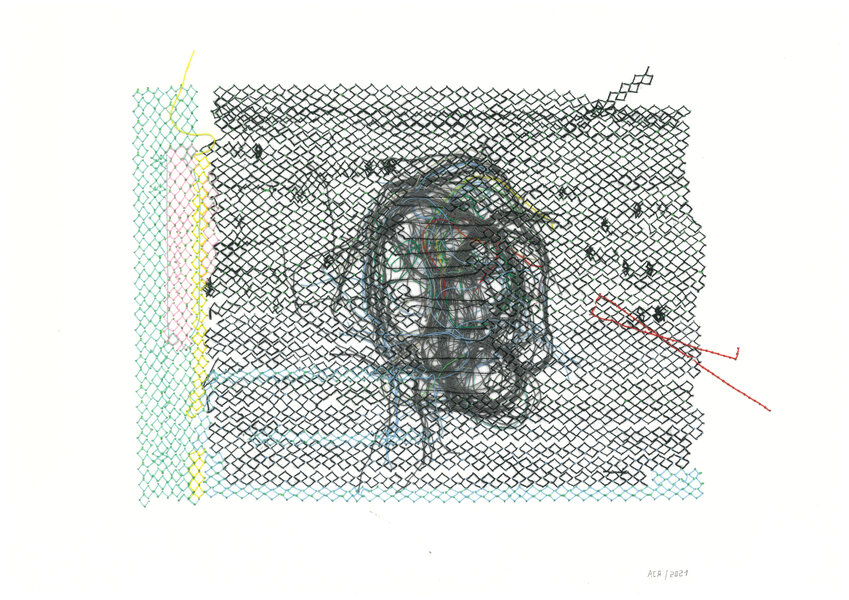

The story told in Iron Overtones is about the magnetism of budding friendship that is shyly testing the new boundaries of the relationship. This is when we can share what is most sacred. The adolescent desire for togetherness is so strong that everyone is ready to participate in the potlach, without fully realizing their own and others' generosity. The personal acquires its own shape within the communal by willfully crossing its boundaries. In the desire to become part of the communal body, the individual butts up against the hard and sharp protrusions of reality and thus discovers itself. Marakulina describes the practice of social interactions in her typical reserved and slightly detached manner. By showing the viewer her game, the artist is not suggesting to join in immediately — she is simply demonstrating a degree of trust.

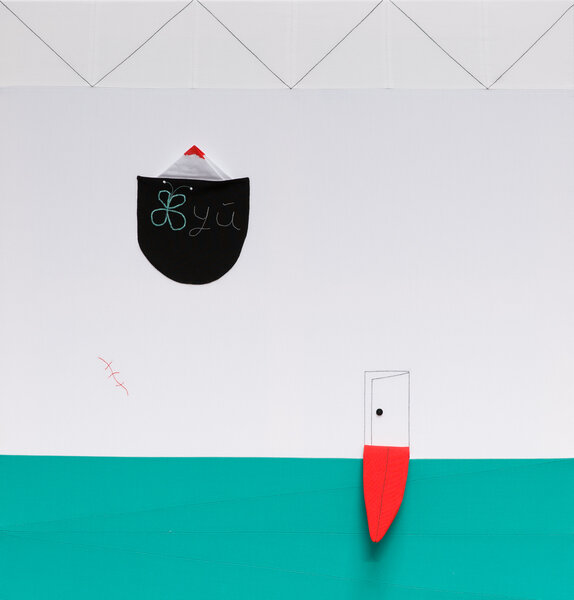

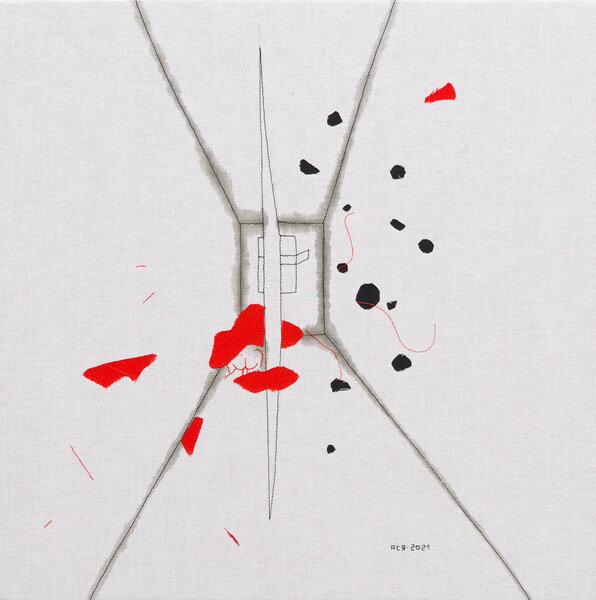

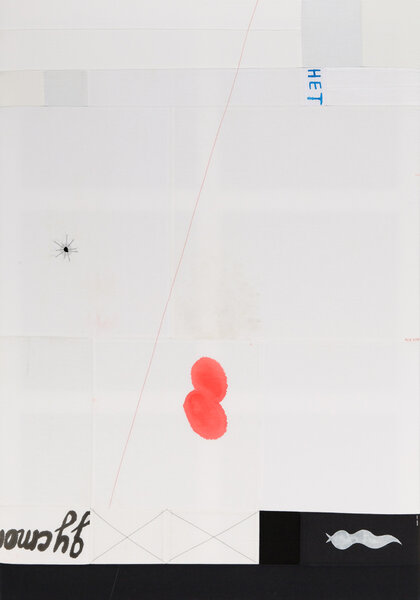

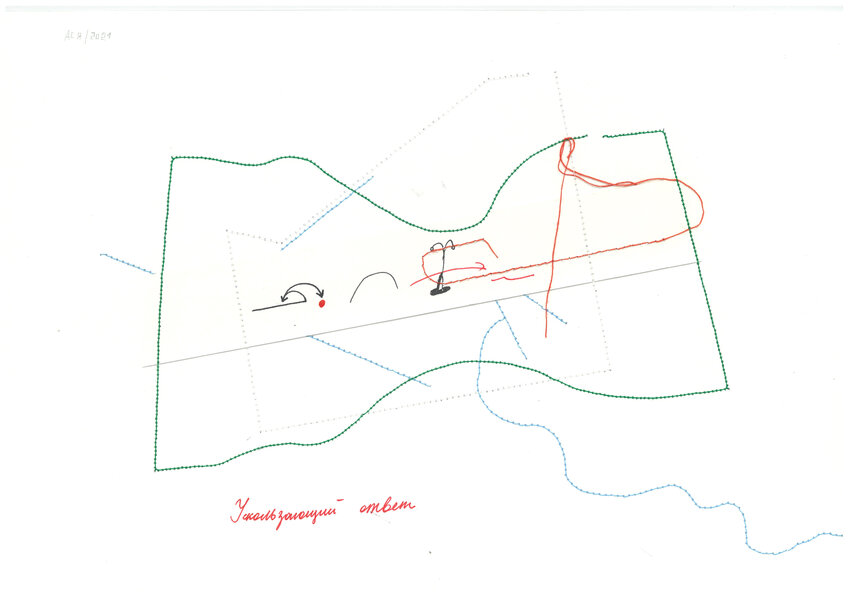

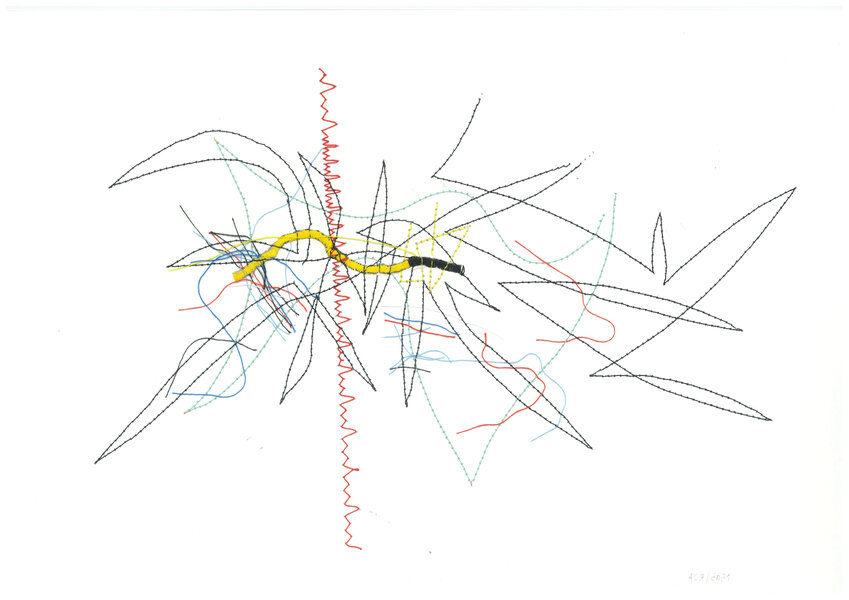

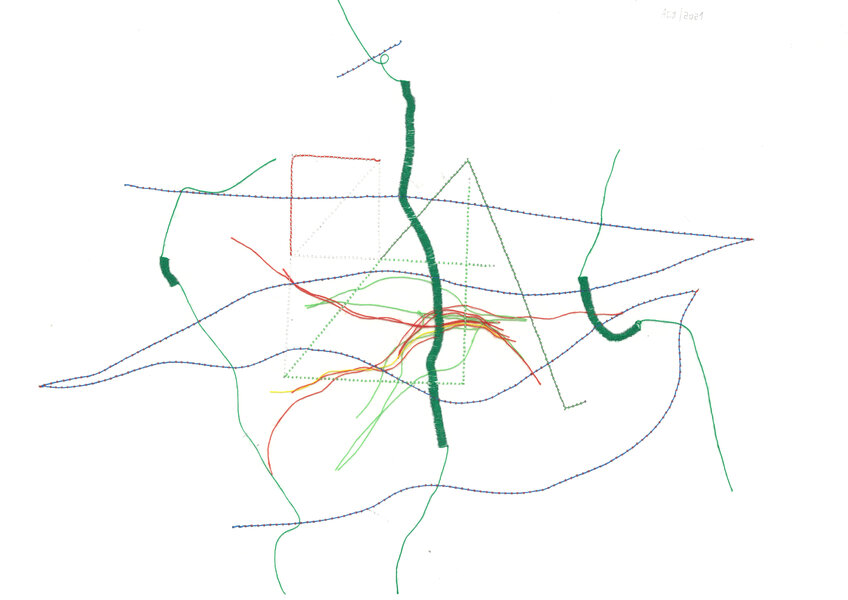

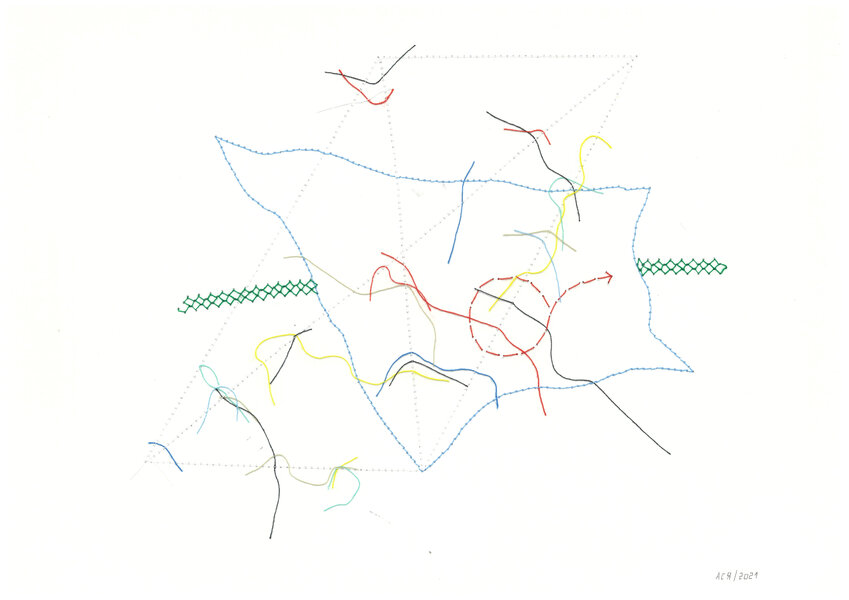

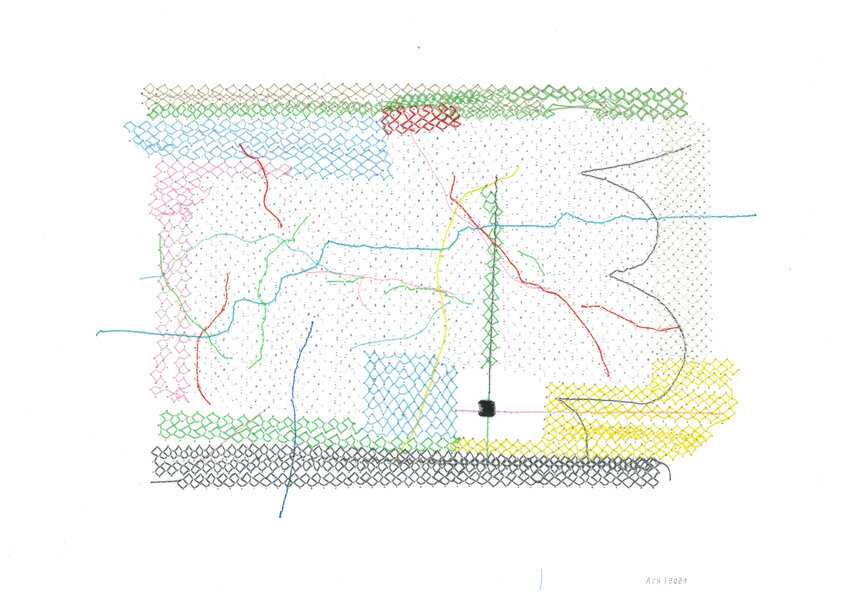

The external projection of the internal space is given only the most general coordinates: mock-ups of installations that are also the basis for drawings used to make objects out of the iron rod. The watercolors are filled with air, marked with a grid of iron structures. An animation artist by training, Marakulina strives for scenography in her works. Her drawings are closely connected to objects, including things sewn out of fabric and welded on metal (the transition to this material is an important stage for the artist). Hard objects would seem to oppose soft ones, but all of the created objects exist in symbiosis. The metal objects are predominantly associated with cubist malleability, while the fabric items have a typical surrealistic origin.

The dresses made by the artist have names: Entryway, Straight-A Student, Girlfriends. There is a wall with the bottom meter and a half painted in public housing green, which first appeared in the art of Ilya Kabakov. But in Marakulina's hands it suddenly looks like real clothing, rather than a carnival or theatrical costume. The entryway is turned inside out, the notebook opens to an A+, awkwardly scratched graffiti is transformed into stitches of beautiful embroidery, praise is showered on everyone for completing the assignment, and the house puts on a dress. There is no longer any structural opposition between different types of materials, shapes, or sensations. The internal is made visible and the hard becomes soft, takes on a human size and surrounds the figure.

The story told by the artist demands a broader reading than just a feminist one. It develops around a game plot, describes the formation of friendship and shows how to transform personal experience, like not cutting yourself on a grater and avoiding the corners of iron structures by wrapping the protruding edges with the soft cloth of invented stories. “I have recently been feeling how I am becoming more confident, and when you understand what you want, iron overtones may emerge,” says Asya Marakulina.

Text: Pavel Gerasimenko