Initiation of beasts.

The subject of appealing to the forgotten sources of humanitarian culture nowadays becomes quite important; it tends to fill up the extensive, complicated knowledge. The medieval bestiary is among these sources – the collection of zoological articles with the didactic and moral meaning.

There were several exhibitions with the title “Bestiary” just during recent years.

Generally they are quite far from the mediaeval knowledge themes, but use the mystery and fantastic nature of the ancient culture quite readily.

In case of the new project by Gregory Maiofis the title and the theme of “Bestiary” correspond to each other.

Medievalism has a tradition of perceiving bestiary in the context of Epichristian Physiologus known from 2nd century AD in Alexandria, Egypt. The Physiologus is considered to be “the herald” of the High Middle Ages and is mentioned by the well-known authors: Hexaemeron by Pseudo-Eustathius, in works by Aurelius Ambrosius and Epiphanius.

The researcher A.G. Yurchenko calls The Physiologus the zoological mystery. The reason for this is that in spite of the extensive descriptions of appearance and habits of animal kingdom characters, the book itself is not about the animals at all.

It is a sermon of the Christian teaching and critics of the pagan world coded in signs and symbols. The Alexandrine Physiologus observed some proportion between natural-science and mythological knowledge; in bestiaries the characters are already isolated from reality as much that they become clear metaphors, illustrations of the Christian morality that they contain.

Resources of such metamorphoses are hidden in literature works devoted to wanderings and travelling, where the main characters meet various paranormal phenomena (such as miracle monster whale-fish, sirens etc.). This section of literature was enriched with catalogues of real strange beasts, which were collected in the same Alexandria by Ptolemy II.

Properly speaking, the readers of both the Physiologus and Bestiary are interested today not only in the moral maxima, which the images of the catoblepas, myrmecoleons (ant-lions) or onocentaurs contain but in the exquisite text ligature like in the ancient manuscripts and the figurative image that appears in mind due to the extensive descriptions.

Thereby, let us hazard a guess that Bestiary today is mostly understood from the point of the thought of adventures and traveling themselves, of wanderings full of unpredictable discoveries and meetings.

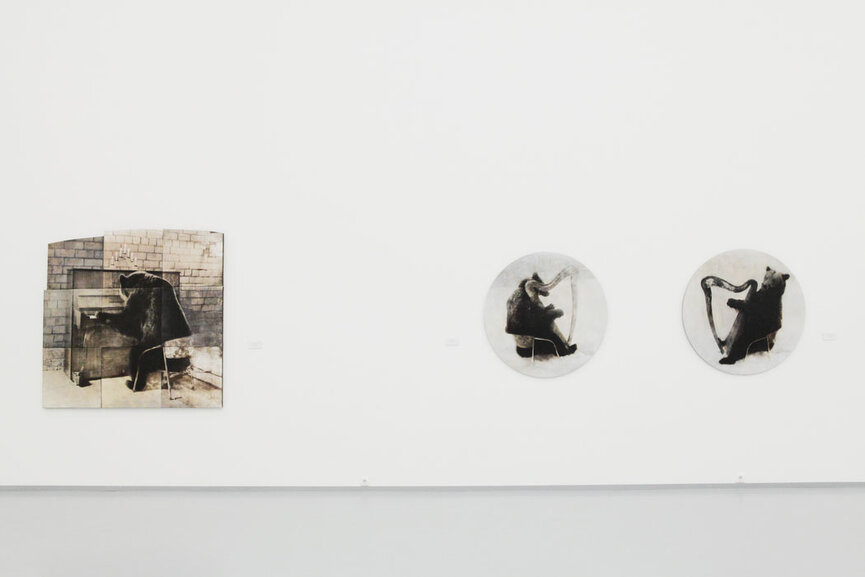

From the position of taste for adventures in the old style there is a sense to appeal to the art of Gregory Maiofis. At once one may be intrigued with the noble time patina that his works are touched with. The artist creates it with the help of the complicated bromoil technique. Bromoil process allows saving the charm of structure and texture of photograph and at the same time strengthening its effect by the means of painting. Russian contemporary art attempts to stylize photography into painting as long as Maiofis tries to present photography as a kind of treasure which is absolutely full-featured from the point of painting quality. This way we see the world as in the very old mirror’s amalgam, where all the objects are deliberately “made old”. It makes them look unusual, unfamiliar and strange.

And this strange nature is the key word for Maiofis’s poetics. It’s curious that the words “strange” and “wander” in Russian language have the single root, isn’t it? The same is with the word “land”. The idea to look at the sort of usual world as if we discovered it in the end of long and hard wanderings is quite charming and teasing. Actually, it intrigues with the same as the texts of ancient bestiaries – the chance to start the way promising the extending of horizons of our knowledge of the world.

The main character of many of Maiofis’s paintings is a clumsy bear, which seems to be very familiar character for us and our cultural tradition. Nevertheless, it is presented in the artist’s works as the archetypical giant, who is dense, chthonic but richly talented with a kind of very human grace. One may certainly explain this gracefulness and “humanizing” of the bear with the circus origin and professional artistic features. These features, not only in case of the bear but also concerning other fable characters from works of Maiofis (they are monkeys, elephants, dogs) state more extensive scope of the dialogue with the pieces.

The artist himself calls his opuses by the analogy with the playful idioms and proverbs. Still the simplicity of presentation is deceptive. The world habited with our fable characters disturbs with this very medieval, “not-fable” complexity of its existence. Here there are no bears and elephants tumbling and pounding the piano keys, it’s the swirling energies of subconsciousness which are deep-laid and often dangerous. They are as strange as the images of the medieval beasts.

It’s curious that one of counterpoints of all books about ancient mythological creatures is the idea the human initiation, when the person in his self-knowledge passes the way from the lower to he higher being shined with the God’s grace.

So, the world of beasts becomes almost the bad example of new ethic and moral valuables of Christianity. The world of Gregori Maiofis carries us into the wandering which is important the same for perception of self nature and where the low and high nature get each other's measure.

Sergey Khachaturov